Reflecting on a Remarkable Story

Lately, I read my first John Hart novel, The Last Child, and loved it. So much so that I immediately ordered two more of his books. Since we just covered a book that failed epically (5 Ways to Wreck Your Novel), I thought that Hart’s book would be a great [spoiler free] way to examine what makes a truly effective story. As we look at what he did so well, I’ll identify 5 ways you can rock your novel!

Synopsis

Johnny Merrimon is a twin…or was. His thirteen-year-old sister, Alyssa, disappeared a year ago. Since then, his father has also abandoned Johnny and his mother, leaving them destitute, his mother an addict and Johnny desperate for answers. The boy has made it his mission to explore even the darkest fringes of society, seeking for any evidence of his sister’s whereabouts. Meanwhile, detective Clyde Hunt, a man still haunted by the unsolved case of Alyssa’s presumed abduction, grows increasingly concerned about Johnny’s activities and the places to which they will likely lead him.

This is a mystery, making it an excellent counterpart to the supposed mystery we discussed in my prior post.

Give Readers a Unique, Larger-than-Life Main Character

Johnny jumps off the very first page of the prologue. He’s on a bus, alone. Through the driver’s eyes, we see that Johnny appears to be a runaway, suffering from sleeplessness or malnutrition, with wary, haunted eyes. But when the boy leaves the bus and undertakes his objective (I’ll leave it for you to discover what that is), Hart hits the readers with a heavy dose of shock, horror, despair and empathy, instantly pulling us into Johnny’s world.

Though our initial shock eases into the main story, Johnny remains larger than life from start to finish. He’s a boy who won’t give up, won’t give in, won’t go along, won’t be controlled…you name it. He’s going to find his sister if it’s the last thing he does. If that means driving the car (often) at 14 years old, if it means stalking pedophiles and known predators, if it means sleeping in the woods that’s what he’s going to do.

All of this adds to Johnny’s appeal. He’s easy to care about, but never predictable. And he does change throughout the book in subtle, but measurable ways.

Build a Twisty, Unpredictable Plot

Hart’s plot isn’t predictable either. Whereas another writer would pair Johnny with the wanna-be father figure, detective Hunt, Hart doesn’t. Johnny wouldn’t have it. He’s going to do things on his own. Whereas another writer would lead the boy to discover what seems like the only possible answer and end the book there, Hart delivers a striking twist and takes the story in another direction.

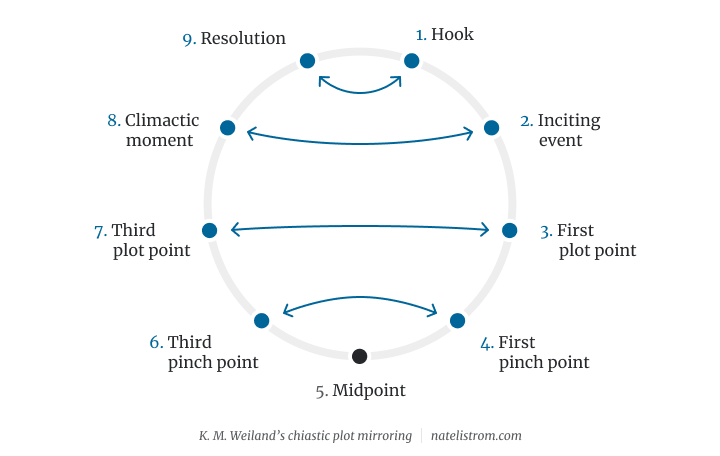

I can’t give you too much here or I’d have to give some spoilers, but suffice it to say that Hart’s plot is a solidly unpredictable and yet satisfying one. As you’re building your own plot, the best advice I can give is to know the ending first and then work backwards from there. Build in twists by heading in a different direction than the ending you intend; then twist it in another direction; twist again until you have readers sitting squarely where you originally planned on ending the story.

Know What Readers in Your Genre Expect/ Require

We talked about this at a higher level in the mirror post – 5 Ways to Wreck Your Novel – but I’ll give you some more genre-specific details here.

The Last Child is a mystery with a healthy dash of thriller. What makes it a thriller is that Johnny has a nemesis who sees such an enterprising, determined and tenacious young man as an obstacle to the control he hopes to retain on Johnny’s mother. He intends on removing Johnny from the equation and sets out to do that in increasingly malicious ways. In this story, readers will expect to see both mystery- and thriller-specific elements. Some of those are:

- An opening mystery – Alyssa is missing and presumably abducted due to an eyewitness account; readers know this at the beginning of the story

- Search for clues – Johnny spends the book searching for clues to her whereabouts and narrows in on the truth as the story progresses

- Known threat – the nemesis in the story escalates his pursuit of Johnny throughout the book

- Sidekick – many genres benefit from a sidekick, often, but not always, a contemporary of the protagonist (one of Johnny’s friends in this case), with whom he can share the journey and explore possible clues

- Mentor – mentors are practically required in Fantasy novels (here’s to you, Gandalf!) and very often in any genre in which the protagonist is a child

- Main Character’s triumph – the MC must, must, must solve the mystery. Some writers make the mistake of allowing the mentor or another character to jump in and at least help in the solution. That is a huge no-no! There’s a reason why mentors are very often eliminated from the story (often at the 75% point) or at the very least their influence is significantly diminished. Readers expect the main character to overcome the challenge.

- Who can be trusted? – in a thriller this is a requirement. Thrillers are about the question of trustworthiness: who is who they say that they are, who will come through or support the main character versus who is really untrustworthy?

- A fast pace – this is often true in mysteries, but much more so in thrillers.

Hart gives readers all of the above.

Keep the Tension/ Conflict at a Constant Pitch

As I just implied, Hart gives readers nearly constant tension and conflict. There are times in even the most intense stories when an author gives the character(s) a moment of relief from the conflict. The extent of the story’s tension is a balancing game. Too little and readers lose interest; too much and the author risks losing them to exhaustion and undue stress.

Hart walks that line very effectively. If anything, he maintains the utmost tension that most mystery-thriller readers will tolerate. That makes the book unputdownable as we now say in the literary world.

If in doubt, amp up the conflict and tension, not down. I’ve never seen an author give too much, but the alternative is a death sentence for the book. And keep in mind that even though you, as the author, know the book’s ending and aren’t surprised by your own twists and turns, if it doesn’t give you a sense of suspense or wonder or adrenaline (whatever you’re going for), it won’t give your readers one either.

Nail the Ending

And lastly, Hart nails the ending, which is absolutely essential. You can have a flawlessly crafted book, but if the ending doesn’t wow readers, they’ll hate the book. It’s that simple: the ending is a deal-breaker. Obviously I won’t tell you what the ending is, but I’ll give you some high-level pointers regarding how Hart accomplishes this and how we should as well.

- Fitting: It has to fit all of the pieces you’ve given the readers. That means that everything the protagonist has discovered and experienced should lead to the ending.

- Unexpected: In some genres such as mysteries and thrillers an unexpected ending is required. When we pair that with our first point above (fitting), that means that we’ve laid out all of the clues, but our main character and our readers haven’t put them together properly until the very end. I’ll say that again: the clues have to be there. Don’t give us a surprise ending that no one could have guessed. Everyone hates that. BUT, do give us enough red herrings, combined with the MC’s misdirection so that we don’t interpret the clues correctly.

- No Loose Strings: Every loose string should be tied off in such a way that it feels natural. They all wrap up easily, smoothly, without being forced. The only exception to this is if the story is part of a series of books and some of the strings (and the principle conflict) have to remain open until the final book is finished.

These are tall orders. They’re hard things to accomplish, but they’re the difference between an effective novel and one that isn’t. Hart does all of them well in The Last Child. If you haven’t read it, check it out!

If you enjoyed this post, share it with your friends!