How You Can Use These Plot Structures

Circular plotting is an oft-used means of structuring a book. A ring structure, also known as a symmetrical plot or a chiastic structure, is a lesser known, but more detailed structuring device. If you’ve ever been confused about the differences, how to use them or why you’d want to use one or the other, you’re in the right place. Stay with me as we examine both circular versus symmetrical plotting.

Circular Structure

If you watch movies, circular plot structures are already part of your intuition, regardless of whether or not you’ve recognized it. I’d be willing to bet that most if not nearly all movies have something of a circular structure. Why? Because it feels complete.

The essence of this type of plotting is that the protagonist’s journey starts and ends in approximately the same place (either the setting itself and/or the type of situation) and yet the character has changed and the conflict is over. I’ll give you an example.

Plot Spoilers Ahead!

War Horse

War Horse is a World War I movie about a young farm boy, Albert, in England who enlists after his beloved horse, Joey, is conscripted by the military. This heartfelt movie is the tale of their bond and ultimate reunion.

The movie begins with the hardships of the main character and his family on their failing farm. To make a long (but good) story short, the protagonist’s father buys this splendid but impractical horse at auction. However, Albert bonds with the horse and manages to train him to plough their fields, saving the family from bankruptcy.

That would be a short story if it wasn’t for the war. After all of the drama of the battles and his fight to survive, Albert is reunited with his horse. In the last scene of the movie, he and Joey return home to the family’s farm. That’s what makes this a circular plot: the beginning shows Albert’s trials on the farm, his lack of maturity and the loss of his horse. The ending shows him returning to the farm wiser, reunited to his horse and [as it’s implied] certain to triumph going forward. The story comes full circle.

Ring/ Symmetrical Structure

A ring/ symmetrical/ chiastic structure—three terms that refer to the same thing—takes this circularity to a much greater degree. At its essence, it’s a plotting structure in which the second half of the book (or series!) mirrors the first.

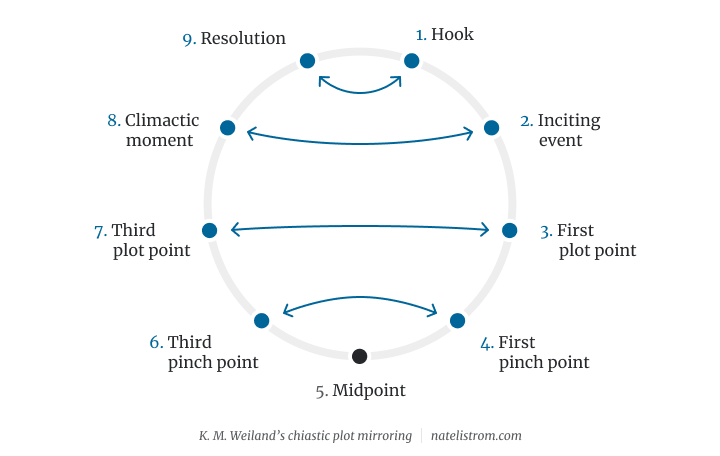

I particularly like Nate Listrom’s graphic (above) which he based off of K.M. Weiland’s series of articles about chiastic or symmetrical structuring. You can find more of her articles about employing this structure here:

Notice from above that the reader should see (regardless of whether she consciously notices or not) the resolution as a reflection of the hook, the third plot point as a reflection of the first one and so on. This doesn’t mean that the two are two versions of the same incident. Rather, in the opposing one, the author shows how the characters have changed by giving readers a different view of the same type of incident. We’ll get into more of that below.

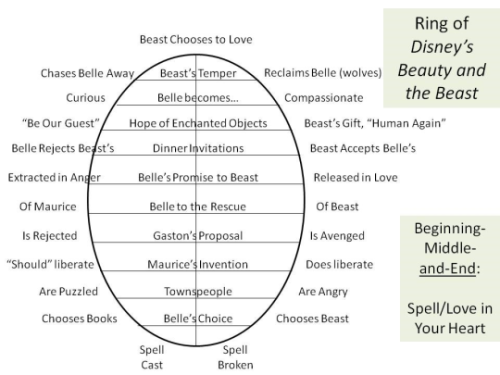

This method isn’t necessarily restricted to major plot points. It can be carried down the scene level. Susan Raab’s graphic of the 1991 movie, Beauty and the Beast, is a great example of a story that uses a scene-by-scene symmetrical structure.

In order to help you interpret this, especially if you haven’t seen the movie or it’s been awhile (frankly, it has been awhile), the story begins at the bottom middle point, and then progresses clockwise. For example:

- At the beginning of the story the spell is cast: a witch transforms the prince into a beast

- The writers show Belle choosing books above everyone else

- Viewers see the response of the townspeople (they think she’s strange because she isn’t content with the provincial life that they enjoy)

- etc.

…after the midpoint, when Belle chooses to love, each of the story’s subsequent actions mirrors those in the first half. Some of these are:

- Rather than Belle rejecting the Beast’s dinner invitation, as she did in the first half, she invites the Beast to dinner (he accepts)

- As Belle had rescued Maurice (her eccentric, inventor father) early in the story, at the opposite point in the story (timing-wise) she comes to the Beast’s rescue

- In the end, Belle chooses the Beast over books

- As a result, the spell is broken

The Mirror

As you can see, some of these events are more reflective (two views of the same type of event) rather than opposing. However, regardless of how the mirroring works, it acts to show change. Look at each of the events above (from Beauty and the Beast) and note how the writers show both Belle and the Beast growing in different ways.

For example, Belle is particularly insular prior to her imprisonment in the Beast’s castle. Early on she comes to her father’s rescue by following him to the Beast’s castle and offering herself as the prisoner in his place. Later she comes to the Beast’s rescue as the townspeople seek to destroy him. These two scenes seem virtually identical with swapped recipients of Belle’s benevolence. But on closer examination, we see that Belle is stepping out of her provincial world—the very thing she said that she wanted to do in the very first scene—and coming to the aid of someone who isn’t a family member.

In another example, note the Beast’s character growth. In the first half of the story, he imprisons Belle in her father’s place. This is consistent with his selfish and ruthless character at the start of the story. However, later he releases Belle so that she can rescue her father [again!]. We see his concern for both of them—a distinct difference from the beast we knew at the beginning.

While these two examples are both very character-centric, other mirroring incidents are more plot-centric such as Maurice’s awkward wood-chopping invention in the beginning that leads him to his imprisonment. Later though, Chip is able to use that invention is to rescue Maurice and Belle from the cellar.

The Value of Symmetrical Plotting

This type of symmetrical plotting feels balanced and satisfying. For one, readers detect that each of the open threads in the story is fully addressed. Each time you show them a before picture of the character, they later receive an after image that closes the loop.

For another, it gives meaning to every aspect of the novel. That funny scene with Belle’s father and his wood-chopping invention comes full circle in the end. It ends up being one of the necessary keys to their escape. Rather than being simply comedic, it’s there for a reason. Readers love when everything has meaning. I think that’s intuitive. We want to see all of the portions of our own lives have meaning and often, even if we believe that they do, we don’t see or understand what those meanings are. In literature, readers want that satisfaction.

How Can We Use this Type of Structure

The key to doing this well is to understand the heart of the story.

Action Plots

Action-driven plots are more straightforward and the symmetry will be as well. However, you don’t want to have exact replicas of each scene in the second half of the story.

Let’s say you’re writing a story about an art heist. Your protagonist is a master thief. In the beginning of the book he steals a car so that his identity is covered in case someone tails him. However, the robbery goes wrong in many ways, including his car being impounded. At the end, he fools the security mastermind who believes that his art gallery is foolproof and gets away by stealing his Lamborghini. He could have escaped in any number of ways, but using another stolen car resonates with his history in a satisfying and humorous way.

Character Plots

If you’re writing a more character-driven novel, perhaps a Horror story (yes, Horror is a character genre; you can read about the relatable, human underpinnings of the genre here: The Relatable Side of Horror), you’ll want to get at the heart of the character’s growth.

Let’s say you’re writing a story about a woman who’s haunted by a female ghost. The story escalates from small-scale torment to life-threatening physical attacks. Readers eventually learn that the protagonist has a history of self-centered actions that often betrayed the confidence and trust of others, especially her supposed closest female friends. This reached a high point many years prior when she abandoned a friend in need so that the other woman had to make her way home alone from a party in the middle of the night. As a result, her friend was brutally raped and murdered. It’s this woman’s ghost who’s now haunting her.

Of course, if you understand the bones of the Horror genre, you know that the ghost is really just the tangible form of the protagonist’s guilt. She knows that she’s in the wrong (or should) and she hasn’t dealt with her former actions. Because of this, the guilt has finally reared its head and is going to traumatize her until she confesses or atones for and amends her ways.

All of this information is crucial because it will dictate how you build a symmetrical structure. In the first half of the book, your main character is simply reacting to this new violentr force in her life. She’s running from it, maybe trying to understand it, denying it, etc. but she isn’t battling it. Not in any sense of actually owning up to her prior guilt.

However, after the second half of the story, she begins to engage in the conflict in a more active way, which includes uncovering the guilt that she previously buried and has since denied. Your symmetrical scenes might look something like:

1st half: perhaps in her workplace she overtly throws someone under the bus or damages this other person’s reputation by allowing a false assumption to go unchallenged because it would cost her something.

2nd half: she goes out on a limb to side with someone, placing herself in the hot seat with them because she knows that this person is in the right, or has been wrongly accused of something.

1st half: maybe she’s having an affair (notice that this is consistent with, but different from her primary problem: her unfaithfulness and selfishness; you’re examining and demonstrating her flaw from multiple angles). Her husband is blithely unaware and is the laughingstock of the neighborhood. He senses that something is wrong, but is ignorant to his wife’s actions.

2nd half: she sees the error of her ways and breaks off the affair. She confesses all to her husband, knowing that it might be the end of her marriage, a relationship that she desperately wants and would hate to lose.

Timing

Notice that none of these examples are truly revolutionary. Most of us know to include this sort of round closure in our stories. However, that doesn’t mean that we always do so as completely as a symmetrical story requires. It also doesn’t mean that our timing lines up with the symmetrical/ mirrored structure that we saw above.

A symmetrical/ ring/ chiastic plot structure uses this type of mirroring in exact (or nearly exact) timing. Meaning that if that opposing scene happens at the 5/8 point, the symmetrical scene should have happened at the 3/8 point (directly opposite one another in the two halves of the story).

There’s a certain instinctual satisfaction when the reader experiences this symmetry. It’s like a circular plot. We use this type of structuring because it reads well. It feels good to the audience. The pieces are all in order, the story is complete.

Conclusion

Using a symmetrical plot structure is a choice. You don’t have to do so, but the rewards are evident. The popularity of books like the Harry Potter series that’s symmetrical at the scene level across the entire series (yes, across books) is undeniable and much of that is probably due to the satisfaction of the tight plotting.

In addition, symmetrical plotting gives the writer a huge advantage: it tells you what you need to do across the entire story. If you open with that work scene in which our character implicitly betrays a coworker, or that art thief steals a car, you know what type of scene to include in the second half of the story and exactly where to place it.

The key is to brainstorm ways (especially in a character-based story) to open or close that loop so that the scene reflects the heart of the opposite one without looking identical and while showing the appropriate degree of character change for that point in the story.

I find this means of plotting extremely liberating, but I have a very structured personality and I thrive off of plans. I recognize that it’s not for everyone, but give it a try and see if it works for you. If so, it can only help you. And if you have used this type of plotting before, let me know. I’d love to hear about your experience!

If you enjoyed this post, share it with your friends!